Counting our chickens: US negotiating objectives and UK trade policy

The United States Trade Representative (USTR) has released negotiating objectives for a prospective Free Trade Agreement (FTA) with the UK. The publication of such objectives is a routine event before the US enters into any trade negotiations. But it made headlines in the UK, which has little or no direct experience of trade negotiations. The scope of US objectives seems to have caught politicians and commentators unaware. The sense of trepidation, if not alarm, was accentuated by the US Ambassador’s comments that the US demands, particularly in sensitive areas like agriculture, were “no brainers”. The idea that chlorine-washed chickens from the US will find its way into UK plates has caused a collective shudder. In this article we argue that the reaction in the UK is more a commentary on the state of trade policy (or lack thereof) in the UK, and discuss some of the policy implications.

You’re playing with the big boys now

The statement of negotiating objectives published by the USTR is partly for domestic consumption. It is done pursuant to the legal framework within which the USTR operates. It is also a signal to partners of the US’ “opening offer”. There should have been no surprise at the nature or content of the statement. The objectives for the UK was preceded by a statement of objectives for the European Union, in January 2019.

The objectives for the UK are for the most part a verbatim restatement of the objectives for the EU. That makes sense since the UK has inherited the EU’s trade policy as its default setting. Areas that have caught most attention include agriculture and sanitary and phyto-sanitary measures (SPS)[1]. There are some cosmetic differences in wording in the introduction: in particular, the statement for the EU speaks about reducing the bilateral trade deficit between the UK and the EU. The main substantive difference is in the area of intellectual property, where the objectives are much more detailed for the UK. But overall, the objectives show that (aside from the few areas where tariffs are still relevant) negotiations with the US will be generally about regulation, whether in goods or services.

A reading of the US statement of objectives for the EU should have prepared the UK for what was to come. That the UK seems to have been caught on the hop may reflect, besides inexperience, a lingering sentiment that the UK would be treated differently. Politically, the idea that Brexit would leave the UK free to glide to the US’ warm embrace had been touted by politicians in favour of “harder” versions Brexit, and also by President Trump himself. The objectives should put paid to the belief that sentimental notions of “special relationships” carry any weight in the mercantilist world of trade negotiators. Indeed, if FTA negotiations between the US and the UK and the US and the EU were to proceed in parallel, they may provide a useful natural experiment as to how differences in size can affect negotiating outcomes.

Others have red lines too

As already observed, the negotiating objectives represent an opening gambit. But there are some issues that are firmly entrenched in the minds of US negotiators, and that are carry-overs from decades of tussles with the EU. If the US has reproduced them in its dealings with the UK, it is not because it will treat the UK differently, but because it expects that it will be able to extract a different outcome.

Agriculture is one of these issues. US farmers represent key political constituencies, and have long resented the combination of tariffs and non-tariff measures they see as constraints to their market access in the EU. Accordingly, the objectives call for the elimination of tariffs, and the reform of SPS regimes. On the latter front, the main target for the US has been the EU’s precautionary principle, which the EU has invoked to ban US exports of hormone-fed beef to the EU and poultry processed by chemical treatments (including the now celebrated “chlorine washing” of chickens). A WTO challenge to the EU regime for hormone-fed beef led to a finding in the US’ favour, on the grounds that the EU regime was not risk-based. But the EU refused to budge. A cycle of retaliation and countermeasures ensued until the EU consented to increase its quota of non-hormone fed beef as part of a mutually acceptable solution. But without moving on the matter of precaution. A dispute on the poultry ban is still under way.

The EU has said food safety, and agriculture more generally, are “off the table”. Its preference is for any deal with the US to focus exclusively on industrial goods. Public sentiment in the UK seems to be on the side of precaution: there seems to be little appetite for chemically treated poultry or hormone fed beef. But once the UK leaves the EU, it may no longer be covered by whatever bilateral arrangement the EU and the US agreed to sort out their past disputes on food. The UK may go into a negotiation facing the threat of litigation, against a counterparty that knows that it does not have the EU’s heft to withstand a trade war, and that also knows the UK is desperate for an agreement.

At the same time, if the UK were to move more towards the US’ position, it would almost certainly cause problems with its trade to the EU since the latter would want to put in controls to make sure unwanted food products do not leak into the EU. That in turn would have economic costs, and political implications (notably in terms of a frictionless Irish border).

The media focus on agriculture should not detract from the other issues of interest to negotiators. An important one is Rules of Origin – the often complex criteria that determine whether a product is eligible for preferential treatment under a FTA. The rules are important in a world of cross-border supply chains, and the US has been increasingly keen to use them as a means of repatriating production to the US. This was a key features of the recent US-Mexico Canada agreement. The objective was to both move production from Mexico to the US and ensure China’s participation in supply chains was curtailed. From the UK’s perspective, liberal rules of origin are vital to its interests if it wants to retain efficient cross-border supply chains with the EU. And clearly investors operating cross-border supply chains between the UK and the EU will view the UK much more favourably the more closely integrated the UK and the EU are.

Sell it on services?

Should the UK focus more on services? After all, its services exports to the US exceed its goods exports. This would require suspending disbelief since goods (industrial and agricultural) really do matter to the current US administration because workers in both sectors are core sources of political support. But even setting this aside, the services sectors pose various awkward challenges for the UK.

Recall that the main aim of services negotiations is to remove policies that limit market access and that create discrimination between services suppliers based on nationality. Now both the UK and the US have amongst the most liberal services regimes in the world. The remaining restrictions in the UK are primarily in areas such as professional services, or in audiovisual and media services. Focusing on the latter two, sensitivities reflect the fact that many measures (such as local content requirements in audiovisual, restrictions on advertising, public ownership) are all embedded in a much broader regulatory and public policy frameworks. The notion that modern trade negotiations are negotiations on regulations is nowhere more evident than in services. Not only are these issues politically sensitive, they are embedded in a much more complex cost-benefit trade off than can be captured by mercantilist negotiators used to bartering market access for, say, beef in return for access for cars.

The EU single market has over several decades managed to develop a level of services liberalisation and regulatory convergence that, while patchy, is deeper than exists in any other free trade agreement. That process, led in part by the UK, has required a shared commitment to a set of political and policy values. If the UK were to seek a services agreement of any depth it would require a similar sort of alignment in policy values with the US. In the sectors mentioned, and others such as health services, such an alignment seems far off indeed.

That alignment may well be what die-hard proponents of a deal with the US would like to see: it would involve a rejection of a European approach to public policy to an American one that is seen to be more laissez-faire. But if that is the case, proponents should be explicit about their political objectives, and not couch them in the language of trade.

What’s it all worth?

At times a UK-US FTA has been touted varyingly as an alternative to the UK’s membership of the EU, and as a way of increasing the UK’s negotiating leverage with the EU i.e. by showing that the UK has outside options. The issue has been covered in detail in other articles. We restate the key findings below.

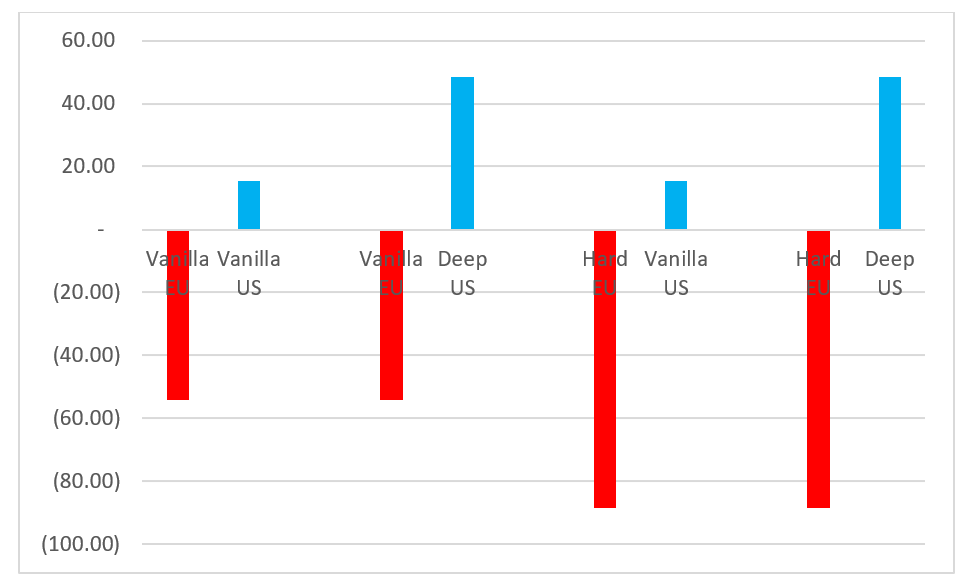

Figure 1 below presents the results, using a gravity model of trade, which is generally recognised by trade policy specialists as a key part of sensible trade modelling. The red bars give the losses to the UK associated with moving from current arrangements to a vanilla deal with the EU or no deal. The blue bars give the gains associated with either a vanilla or a deep agreement with the US.

We see that in no arrangement does a FTA of any depth with the US offset the losses of moving away from deep integration with the EU. Even if the UK were to negotiate a Canada-style FTA with the EU and negotiate a deep one with the US, it would still face some (small) losses. Note that this is on the extremely optimistic assumption that the UK could negotiate and implement – on the point of leaving the EU- an agreement with US of the sort that has not been see outside the European Economic Area, the rules of which took decades to negotiate. Moreover, as explained before, negotiating such a deep agreement would involve substantial changes to public and regulatory policy, and it is questionable how much appetite there is for this.

Moving beyond the figures, the UK’s position is complicated by the fact that it does not know what its default position is. That is partly because of continued uncertainty about the shape of its future arrangement with the EU. But it is also because the UK has still no trade policy of its own to speak of. In his keynote address launching the TKE initiative in 2018, Pascal Lamy said that an essential starting point for the UK was to work out what infact are its trade policy priorities. But because the discussion on trade had largely been a political battle by proxy within the ruling Conservative Party, such a deliberate trade strategy has to date not taken off.

A good example of this is recent debates within government as to what the UK’s tariffs should be were it to leave the EU without a deal. The treasury favours eliminating tariffs to mitigate the impact on consumers and on supply chains. As, outside of a deal with the EU, such tariff elimination would need to apply to all trade partners, sectors (such as farming and certain industrial activities) currently sheltered by the EU’s common external tariff fear they will not be in a position to compete.

Moreover, from a negotiating point, such a move would unilaterally give the UK’s negotiating partners what they want. Vis a vis the US it would shift negotiations even more squarely onto regulatory matters. No economist favours keeping tariffs to increase negotiating “coin”. But the discussion does raise the question of whether FTAs with partners such as the US are really a relevant consideration when so much of the UK’s trade policy needs ironing out. And with the state of the UK’s relationship with the EU causing long-standing business concerns to morph into high and open anxiety, the statement of negotiating objectives issue by the US may be a timely reminder that the UK’s priorities may need to lie elsewhere.

[1] That is, measures to ensure food safety and to protect animal and plant health.