Customs arrangements and post-Brexit trade policy: What are the options?

Customs arrangements and post-Brexit trade policy: What are the options?

Theresa May’s cabinet has met this week in another of its recurring “crunch meetings” on its future position vis a vis the EU. The main bone of contention is the question of customs arrangements. Theresa May has already ruled out continuing membership of the EU’s Customs Union. In place of this, her preference would be for the UK to negotiate a “new customs partnership”.

This proposal was first floated in the Government’s White Paper on Customs in 2017, which suggested that the UK could “mirror” EU customs arrangements with third parties, without providing much detail of how this would work. The idea seems to be that the UK would apply EU tariffs and collect revenues on goods entering the EU via the UK, even if at a future date the UK were to apply tariffs that are lower than the EU’s (for example, if the UK were to negotiate a free trade agreement (FTA) with a country that does not have an agreement with the EU). Normally, countries apply rules of origin to determine whether a product qualifies for duty free or preferential treatment: But the UK fears that implementing such rules would add to the cost of trade between the UK and the EU; hence the proposal for a partnership.

There is some limited precedent for these “dual” arrangements. Switzerland and Lichtenstein have a customs union, but Lichtenstein is part of the European Economic Area, while Switzerland has more limited agreements (its trade agreement with the EU mainly covers industrial goods). This requires arrangements under which Swiss authorities collect taxes and then rebate these to importers if the goods are consumed in Lichtenstein.

Dissenters within the cabinet argue that this partnership approach is unclear and unworkable. They see it as a de facto continuation of the EU’s Customs Union. They prefer an alternative approach, briefly canvassed in the government’s 2017 White Paper, based on enhancing arrangements that are already well established in trade facilitation internationally. These arrangements– single windows, expedited processes for trusted traders – could be supplemented by an agreement that duties would be paid on at specified periods (rather than on every crossing). The approach has been dubbed the maximum facilitation – “Max Fac” – approach.

The Customs Crunch

What makes the normally staid matter of customs administration such a hot topic? For the pro-leave camp, one of the prizes of exiting the EU is the ability for the UK to run its own trade policy. This means it could either liberalise its external trade regime unilaterally, or conclude reciprocal FTAs with other countries. Neither of these options would be available, at least as far as goods trade is concerned, if the UK were to adopt the EU’s common external tariff.

There are two factors motivating those who think the UK should either remain within, or “mirror”, the Customs Union. The first is an economic one: introducing customs arrangements between the UK and the EU would impose costs on businesses, particularly those with cross-border supply chains. The second is political: new arrangements between the UK and the EU would either introduce a hard border between Northern Ireland and the Republic of Ireland, or would require that Northern Ireland be considered a separate customs territory to the rest of the UK.

First principles

What principles could the government follow in finding its way to a position?

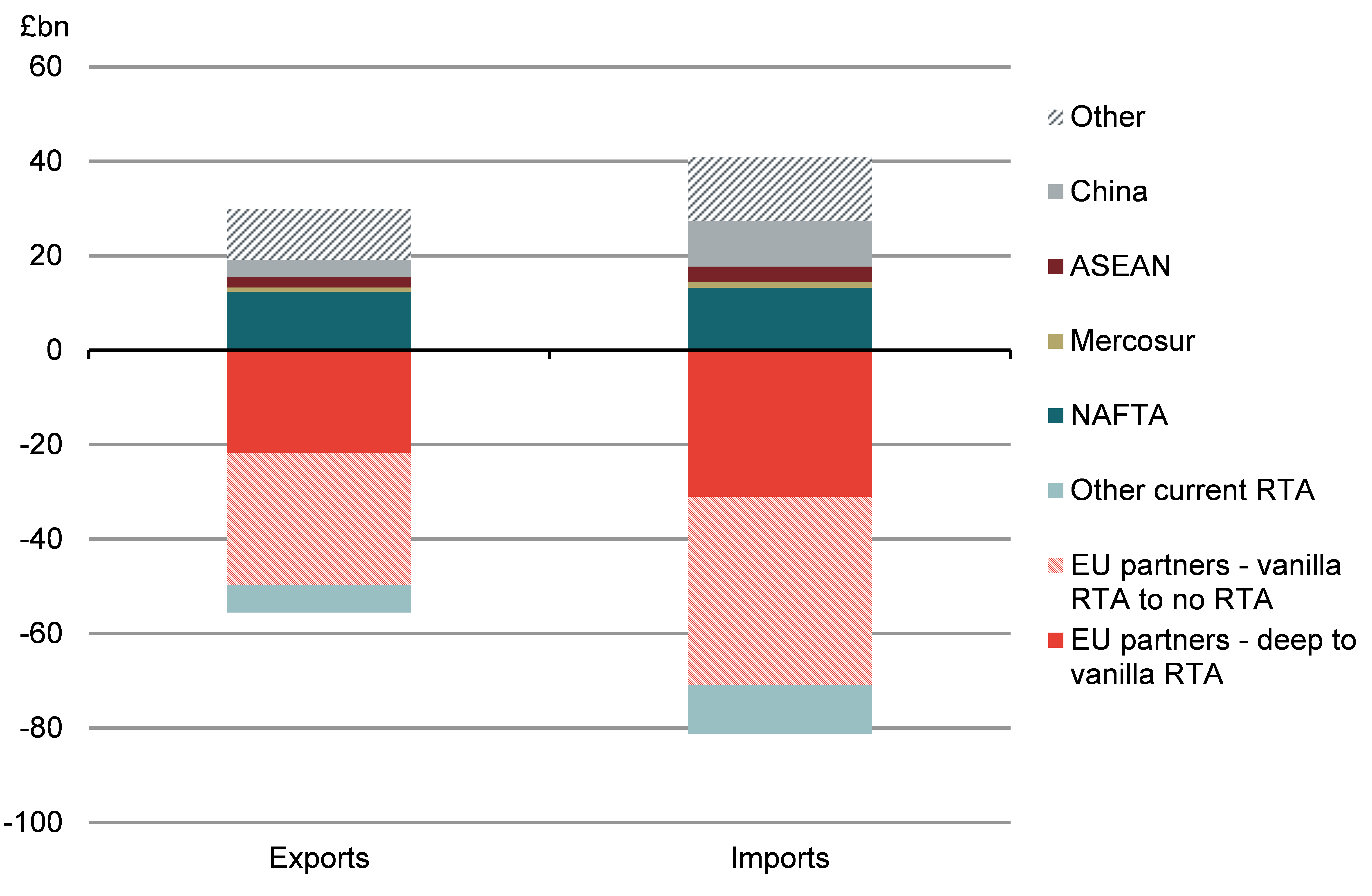

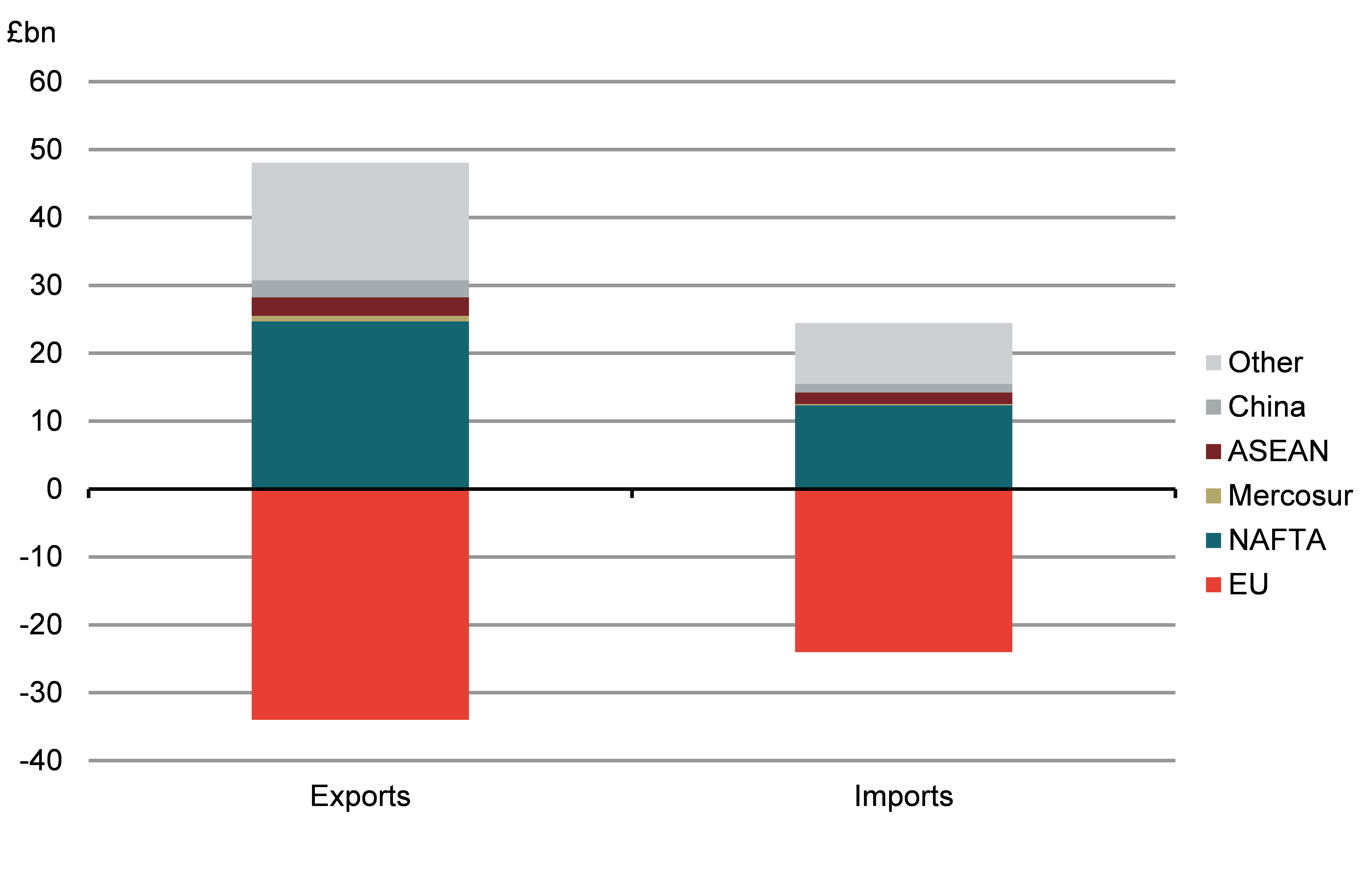

The first is to recognise that maintaining the deepest possible level of integration between the UK and the EU remains a priority. As illustrated in Figures 1 and 2 below, if the future relationship between the UK and the EU were to resemble the type of FTA that currently exists between the EU and third parties, there will be a considerable hit to the UK’s trade in goods and services.

The UK could try and compensate for these losses by negotiating FTAs with the rest of the world, but this requires a heroic set of assumptions. In particular, the UK would need to negotiate at unprecedented speed agreements of unprecedented depth with an unprecedented number of non-EU members (for a deeper discussion see here). And it would need to do so with little institutional capacity or experience in negotiation. Indeed, on current trends the UK would be hard-pressed to even replicate the existing FTAs to which it is party via its EU membership, but which would cease to apply once the UK withdraws from the EU.

These considerations rule out the thesis that an “independent” trade policy outside the Customs Union is desirable as an alternative to deep integration with the EU. They also weigh in favour of the amendment to the EU withdrawal bill, voted by the House of Lords, that the UK should negotiate membership of the European Economic Area (EEA), in the manner of Norway or Iceland. Membership of the EEA would allow for the UK to follow its own trade policy vis a vis the rest of the world.

Which brings us to our second principle: trade policy towards non-EU members can affect the depth of integration with the EU. If the UK were to be part of the EEA, or indeed had any sort of FTA with the EU, and were to conclude FTAs with the rest of the world, it would need to adjust a host of arrangements with the EU. Customs issues and rules of origin are only one aspect. Regulatory compliance could also be a major question. If the UK were to sign a FTA the US, it would need to find a way of controlling the flow of hormone-treated beef (or processed products that used them) into the EU. Such questions also apply to areas services, for example, in areas such as data protection or financial services regulation, in which customs are not a relevant issue.

Overall, the UK would need to weigh up the administrative costs of these arrangements against the putative benefits of an independent trade policy vis a vis third parties. There has been very little research into the extent of these costs to date, nor how they stack up against the benefits of third-party agreements. What can be said is that these benefits remain speculative and some way down the line, while the costs are likely to be more concrete and immediate.

Max Factor versus Max Fac?

If the UK were to conclude a customs union with the EU, it would resolve the problem of “frictions” in trade with the EU. The UK could in principle remain outside the EU’s common commercial policy and negotiate trade agreements on services. But it would face a problem similar to that faced by Turkey – namely that all the trade partners with which the EU concluded a trade agreement would have access to the UK’s market for goods, without the same being true for the UK’s access to trade partners.

Unsurprisingly, reports are that the latest cabinet crunch meeting has not made much headway in resolving the customs question. In fact, it is hard to see how any number of “crunch meetings” can churn out a compromise solution. Those sceptical of a “new customs partnership” are probably right. The concept is nebulous. It’s applicability to matters outside tariff collections is unclear and even on that matter it is likely to create administrative headaches. (How would one demonstrate that, say, fruit from Brazil was intended for consumption in the UK, rather than for processing and exporting to the EU, without driving food manufacturers into an administrative labyrinth?). It could be dubbed the “Max Factor” approach – a cosmetic arrangement designed to gloss over either de facto continuation of the Customs Union or the costs of leaving it.

For its part, the “Max Fac” option may streamline customs administration relative to existing arrangements that apply between the UK and non-EU partners. It has the merit of building on existing principles. But it will hardly overcome the key challenge that lies at the heart of the matter: reconciling the ambition of deep integration with the EU with that of deep integration with the rest of the world, but separately from the EU. It will also need to be tested for compliance with the provisions of the WTO’s Trade Facilitation Agreement. Compliance is more likely if the Max Fac approach is implemented in the context of a FTA of some sort between the UK and the EU.

In the end, the choice is likely to come down to one between retaining the customs union, and more specifically the EU’s common external tariff, or accepting a greater degree of friction between the UK and the EU as a price to pay for following its own liberalisation pathway(s).

None of the options facing the UK, on customs, and on trade more broadly, are costless. The key issue is to mitigate these costs. The best way is to recall the principles sketched out above and to prioritise deep integration with the EU. Agreeing on the House of Lord’s EEA amendment would be a step in the right direction. It would fix a concrete objective for both the UK and the EU. It might also elicit a more cooperative response from the EU, whose collaboration would be required for any approach on customs to work.

On customs, what is needed is a move away from thinking about trade policy in terms of principles that are cherished to the point of becoming dogma (whether these are “independent trade policy” or “friction-free trade”), and towards a more rational analysis of the costs and benefits. Whether such a rational approach can be achieved in the context of an inherently emotive discussion, is a question that has applied since the results of the referendum became known.