Agreement at last

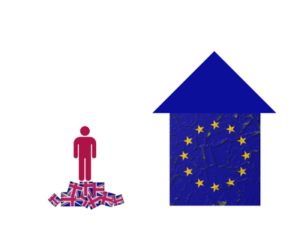

After more than four years of seemingly interminable negotiation following the United Kingdom’s 2016 referendum decision to leave the European Union, the parties finally concluded a Trade and Cooperation Agreement (TCA) at the very last practicable moment, on Christmas Eve 2020. Ratification was rushed through both Houses of the UK Parliament on 30 December, in time for the Agreement to come into force when the transition period ended, at one minute past midnight, Central European Time, on 1 January 2021.

The European Parliament also needs to approve the Agreement, but could not be convened at virtually no notice over Christmas to do so. Also, the constitutions of some member states require parliamentary ratification of treaties. On the EU side the Agreement was therefore applied provisionally.

Mind your manners

Our separate post entitled An ABC of trade liberalisation negotiations analysed the key stages involved in international trade negotiations and suggested straightforward principles for conducting them. Among these principles were advice to maintain good manners and civility at all times; and a final injunction to avoid triumphalism and talking in terms of “winners” and “losers”. Any worthwhile trade agreement is a “win-win” solution bringing balanced advantages to all participants but also necessarily involving some concessions to the priorities of partners. It has to be said that on the UK side in particular and during the four years of Brexit-related negotiations, these two recommendations have not been well observed.

A textbook negotiation

The final stages of the post-Brexit negotiations, though deeply unedifying, were unsurprising and indeed of textbook predictability. Major international negotiations regularly get hung up at the end on just a few final points which may be of relatively minor intrinsic importance and often were not even thought of at the outset, but which respond to specific and vocal sectoral interests. They become tests of national virility and resolve. In the post-Brexit case the outstanding issues were how to secure and enforce a “level playing field” between the parties in regulation; enforcement of competition policy between them; and continued access of EU fishing fleets to UK waters.

That these issues were contentious was not surprising. Indeed they had been flagged as likely flashpoints. They do differ in significance. Fisheries account for less than 0.1% of UK GDP but they have great political clout in a few coastal locations, as also do fisheries in Denmark, France and Spain. On the other hand, level playing field issues affect larger swathes of the economies of both parties.

The issues persisted to the end since both sides resolved to wait until the other blinked. At the same time, and with reportedly as much as 98% of an eventual agreement in place, both the UK and the EU and their senior negotiators had too much national and personal capital invested in the negotiations to be able to contemplate ignominious failure over relatively lesser matters.

The Gordian knot was cut, entirely predictably, at the last moment by an EU concession on enforcement of the level playing field, and a significant UK concession on fisheries. EU negotiators gave up their demand for the right of automatic retaliation in the event of perceived unfair competition in UK business practices. Unable to secure a pact that banned EU fishing boats from UK waters as the British industry demanded, the Government settled for a 25% increase in the UK share of catch quotas in UK territorial waters, to be phased in over five years.

Emergency approval

In emergency sessions on 30 December both Houses of the UK Parliament ratified the terms of the Agreement, the House of Commons by a large majority of 448 votes. There has been no proper parliamentary scrutiny of the text, though scrutiny will unfold issue by issue as the import of the Treaty’s terms sinks in. The opposition Labour Party, which had been overwhelmingly in favour of remaining in the EU, accepted the agreement as the best of a bad job. Conservative right-wingers accepted it but also reluctantly, because they would have preferred a total break with the Union. However they accepted the Government’s rhetorical flourishes about how far the agreement preserved UK national sovereignty intact.

Gesture politics from Scotland

The Scottish Nationalist (SNP) members in the Westminster Parliament voted against the agreement. This was a political gesture because the public and politicians in Scotland have consistently backed remaining in the EU. Some SNP members had an ulterior motive for voting against, because they saw a possible “No deal” outcome with the EU as a further step towards the division of the United Kingdom, and eventual Scottish independence. They ignored the fact that if the agreement had been defeated the resultant No deal outcome would have affected Scotland economically as badly as the rest of the UK. In the event the SNP vote was an empty gesture, as the Nationalists were very far from having enough votes at Westminster to overturn the Agreement.

An unusual treaty

The resultant agreement is a very odd form of trade treaty. Unsurprisingly it runs to over 1240 pages of minutely detailed provisions. But perhaps uniquely, as an integral part of the Brexit process, it is based on terminating open and liberal trade relations rather than creating them, and on erecting practical obstacles to trade rather than removing them. The overriding impression when agreement was finally achieved was not of jubilation but on all sides of weary resignation and relief that the result had not been worse. The UK was not going to crash out of the Single Market with “no deal” and no agreement on future economic relations. However relief is outweighed by dismay at the atmosphere of distrust and rancour in which the final negotiations were evidently conducted, and by ill-judged triumphalism on the part of some of the noisier Brexit supporters in the UK Conservative Party.

Not such a free trade negotiation

Agreement to remove all tariffs and other trade restrictions between the parties is welcome. But it will do nothing to ease the burden of new procedural requirements on both sides of the Channel including Customs declarations, health and safety certification, and the certificates of origin which are now required to establish eligibility of traded goods for tariff-free treatment under the TCA. The CEO of HMRC estimated that the additional cost to UK businesses of filling in all the necessary new forms may amount to some £7.5 billion a year.

Outline of TCA provisions

The Treaty structure is complex. From the point of view of the UK Government, the overriding concern in reaching this agreement was to restore unimpeded national sovereignty – essentially, that after withdrawal from the EU, there should be no direct exercise of EU jurisdiction in the UK at all. Initially therefore the UK side wanted to negotiate a simple free trade agreement (FTA) together with a separate package of free-standing agreements on so-called “thematic” or cross-sectoral issues, obviously with the intention that over time revisions to individual agreements could be negotiated without impacting on the others. This was not acceptable to the EU which insisted on a single treaty with all the different elements balanced within it according to the familiar principle of “Nothing is agreed until everything is agreed”.

Structure

The final document has seven interrelated parts:

- Common and institutional provisions;

- Trade and other economic aspects of the relationship such as aviation, energy, road transport and social security;

- Cooperation on law enforcement and criminal justice;

- So-called “thematic” issues, notably health collaboration;

- Participation in EU programmes, principally scientific collaboration through Horizon;

- Dispute settlement;

- Final provisions.

The body of the Agreement sets out the substantive legal provisions, with operational details incorporated in annexes. For example, the provisions regarding trade in goods are supported by separate Annexes on medicines, vehicles and vehicle parts, organic products, wines, chemicals and agreed standards. There are several annexes on different aspects of fisheries. The UK stresses that agreements which have been concluded in parallel on Nuclear Cooperation and on Security Procedures for Exchanging and protecting Classified Information are free-standing and do not form part of the TCA.

Analysing this content in a different and perhaps more systematic way yields four classes of topics which are covered in the TCA:

- Practical trade-related issues that have been fundamental to trade negotiations over time, such as: Tariffs and quota restrictions (both ruled out under the TCA); technical barriers to trade, and action to prevent their use to distort trade; action against unfair and trade-distortive subsidies; market access for cross-border trade in services and protection of investments; temporary movement of people for business purposes; enforcement of fair competition rules; and fisheries;

- Specific provisions relating to services sectors including: Telecommunications; delivery services; maritime transport; legal services; digital trade; aviation transport rules and aviation safety; road transport; energy; and nuclear cooperation;

- Generic or “thematic” issues relevant to both goods and service trade: A “framework agreement” for the recognition of professional qualifications; capital movements; intellectual property (IP) protection; cyber security; social security coordination; and law enforcement and judicial cooperation;

- “Public policy objectives” provisions such as are now common in international trade and economic agreements: Labour and social standards; environmental protection.

Reduced provisions and terms are set out for the future of UK participation in EU programmes – for example, UK students will no longer be eligible to participate in the Erasmus programme of student exchanges. Detailed provisions are set out for dispute settlement, which the UK side insists are based on international law and not on EU law, so provide no place for jurisdiction in the UK of the European Court of Justice. The Agreement is subject to review every five years, and there are provisions for early termination at the initiative of either side.

Commentary

It is welcome that the UK and EU have agreed to apply no tariffs or quotas on goods traded between them. But as noted above, extensive documentation in the form of Customs returns, health and standards certification and, where appropriate, certificates of origin is now required for cross-Channel trade in both directions. This documentation may be less under the TCA than if there had been no deal, but it will still be burdensome.

It must however be stressed that while the coming into force of the Treaty on 1 January 2021 immediately gave rise to new obligations on both sides, there has not yet been any wholesale change in the nature or volume of EU-derived regulation to which the UK was subject. To avoid as much disruption in trade as possible at the point of effective withdrawal, the UK has incorporated into domestic law the entire regulatory aquis of the EU as it stood at December 31 2020. That, subject to provisions agreed in relevant articles of the TCA, will be the starting-point for such changes as over time UK governments may wish to make to regulation in the UK market.

In any case, whether or not a bilateral agreement was struck, every single UK business or individual seeking to sell goods into the EU or otherwise to do business there will be required to comply with every applicable regulation, standard or required procedure obtaining in the Single Market. When the UK was part of the Single Market there was no argument – British business complied with all agreed rules and trade flowed uninterruptedly. It was the job of Government in the negotiation of those rules to ensure that they were as favourable as possible to UK interests – a job which UK officials did very effectively.

The UK has now given up the security of regulatory uniformity, insisting that it wants to be free to set its own rules and standards. The consequence is that British business trading into Europe now faces a plethora of new procedures designed to ensure that UK products and services sold in the EU will be acceptable according to Single Market standards. If the UK does in the event move away from EU standards which it currently applies, UK manufacturers and traders may find themselves faced with the complexity and expense of developing their products and service operations according to different standards for different markets.

Value of cross-Channel trade

Aggregate trade between the UK and EU (exports plus imports) in 2019 amounted to £668 billion. This represented 43% of total UK exports, and 52% of imports – in all, 47% of total UK trade. Services, which represent 80% of the UK economy, accounted for 42% of UK exports to the EU in 2019.

There’s more to trade agreements than tariffs on goods

The trade statistics mentioned above demonstrate the continuing importance of cross-Channel trade in goods. The TCA is cast predominantly in terms of “traditional” trade policy issues – tariff reductions, elimination of quota restrictions, and the long-established trade-related issues like avoidance of technical barriers, fair and equitable domestic regulation, action against unfair subsidies, measures concerning animal and plant health, trade facilitation in the form of streamlined Customs and testing procedures and public procurement

Yet these issues, while still at the root of modern trade negotiations, are very far from the whole story. Such negotiations nowadays focus increasingly on issues like regulatory and dispute settlement systems, transparency of laws, protection of investments, market access for service suppliers from other countries, avoidance of discrimination against foreign service undertakings in domestic laws, and intellectual property protection, together with the trade aspects of wider issues of public good such as labour standards and environmental protection. All such matters are dealt with to differing degrees in the TCA.

Services sold short

Accordingly the TCA contains chapters on a long list of service activities, as listed above. The UK, having chosen to leave the Single Market in order to escape the “shackles” of EU regulation, has on the whole managed in renegotiating its new bilateral relationship only to secure new ad hoc arrangements that fall well short of the protections which UK services previously enjoyed within the Single Market. There is of course every prospect that, over time and topic by topic, the UK will seek to negotiate improved conditions of access to key EU services sectors, and may succeed in doing so. But many of the solutions now agreed are essentially agreements to keep on talking. This condemns both sides potentially to years or even decades of painfully detailed negotiations on market access issues, much as has been the lot of Switzerland in its dealings with the EU over many years.

Short shrift for financial services

The agreement contains only minimalist provisions on financial services, which are of cardinal importance for the UK, centred on the City of London. There are commitments to go on talking in this sector also, but we have no idea what the longer-term impact on UK banks and on international financiers operating in London will be. Meanwhile both sides have provisionally agreed that in March 2021 the EU will pronounce on whether UK financial regulatory systems are accepted as “equivalent” to those in the EU or not. That decision will be of paramount importance for the City of London and for the entire UK financial sector.

Work in progress

In summary, many of the sectoral or thematic commitments in the agreement amount to not much more than commitments to negotiate further – with the prospect of years, even decades, of continuing bargaining between the parties. The profound irony is that all the negotiating effort up to now, and in the future, is about achieving outcomes and collaborative regimes that fall well short of the agreements and protections which the UK previously enjoyed as a member state. Bluntly put, the UK is trying sector by sector to claw back some of what it has just voluntarily given up. Seen in this light, early pronouncements by Brexit-supporters back at the time of the 2016 referendum, that the UK would be able to secure easily all the trading advantages of membership without any of the restrictions and inconveniences, look even more hollow than they were at the time. No doubt they also had the perverse effect of alerting the EU to the need to protect the interests of its 27 remaining member states and to establish clearly that any country leaving the Union could not expect to enjoy the same advantages as a member.

The myth of absolute sovereignty

Despite all the protestations of ministers about preserving the integrity of UK “sovereignty”, any future bilateral arrangements between the parties must of their nature entail limitations on UK sovereignty. Indeed any international agreement whatsoever which a country enters into, whether bilateral, plurilateral or multilateral, involves such limitations. This is the case for the UK which is a signatory to dozens of operational international agreements, from membership of the United Nations downwards and including a host of agreements, ranging from animal health to telecommunications and space, which set standards by which their adherent members must abide. Countries enter into such agreements for their own good and for mutual advantage and protection. Signing them and agreeing to pool sovereignty or accept an international discipline in some respect is not an infringement of national sovereignty. It is itself an act of sovereignty. And article by article this is the case with the TCA, as indeed it was with the UK’s original adherence to the Treaty of Rome and subsequent treaties.

Half a loaf

This last point is made starkly clear by the operating arrangements which the UK and EU have agreed. The TCA is to be overseen and enforced by a joint Partnership Council which will be served by more than 20 expert subcommittees. That does not sound much like untrammelled sovereignty.

Imperceptibly over the last year or two former Prime Minister Theresa May’s mantra that “No Deal is better than a bad deal” has, with greater understanding, morphed into “Any deal is better than No Deal”. The deal which the UK has finally got is indeed better than nothing, but even with no tariffs or quotas, cross-channel trade in goods is going to be subject to masses of new regulations, customs declarations, origin certification, health checks, etc. none of which apply to trade within the Single Market where all member states operate to agreed uniform standards. The experience of the last days of 2020, with thousands of Europe-bound trucks marooned at Dover because France temporarily closed its borders to the UK for reasons related to the Covid-19 outbreak, indicates what can happen at any time in the future if there is a serious interruption of the flow of cross-Channel trade for procedural or any other reasons. Even given the best of available goodwill, the future for UK business is not going to be plain sailing.