Services are a vital part of the UK’s economy. They account for close to 80% of its GDP. Services exports are around 45% of total UK exports by value, and will in all likelihood overtake goods in the near future. Over the last 10 years, services exports to the EU have grown at an annual average of 5.2%, compared to 3.5% for total trade. Services also play a fundamental role in supporting trade. Think about the role of transport and logistics services in getting goods and components to markets and through different links in the supply chain. Or the role of telecommunications and information technology in facilitating business transactions and electronic commerce. Services are also closely integrated with manufacturing: OECD data suggests that close to a quarter of the value added in UK manufacturing exports is attributable to services.

Services therefore matter. Their significance in the data sits uneasily with the way in which they have been treated in discussions on the UK’s future relationship to the EU. The position adopted by the UK Government was that it would trade off access to the EU single market for services if, in return, it could leave EU disciplines on free movement. That position was largely accepted by the EU and is reflected in the Withdrawal Agreement and accompanying Political Declaration. The fraught negotiations currently taking place between the Government and the Opposition focus primarily on the issue of committing the UK to a Customs Union on goods with the EU. Services have not featured much, if at all.

Liberalisation inside and outside the Single Market for services

The EU’s single market for services remains a work in progress, and EU institutions and services suppliers have at various points called for further liberalisation. But services liberalisation between EU member states has gone much further than liberalisation on a most favoured nation basis (MFN) under WTO rules[1], or that found in free trade agreements (FTAs) outside the EU. Indeed, the latter have mainly focused on binding levels of liberalisation that countries already undertake anyway. [2] Leaving the EU single market on services is therefore likely to increase the level of restrictions faced by UK services suppliers exporting to the EU, and vice versa.

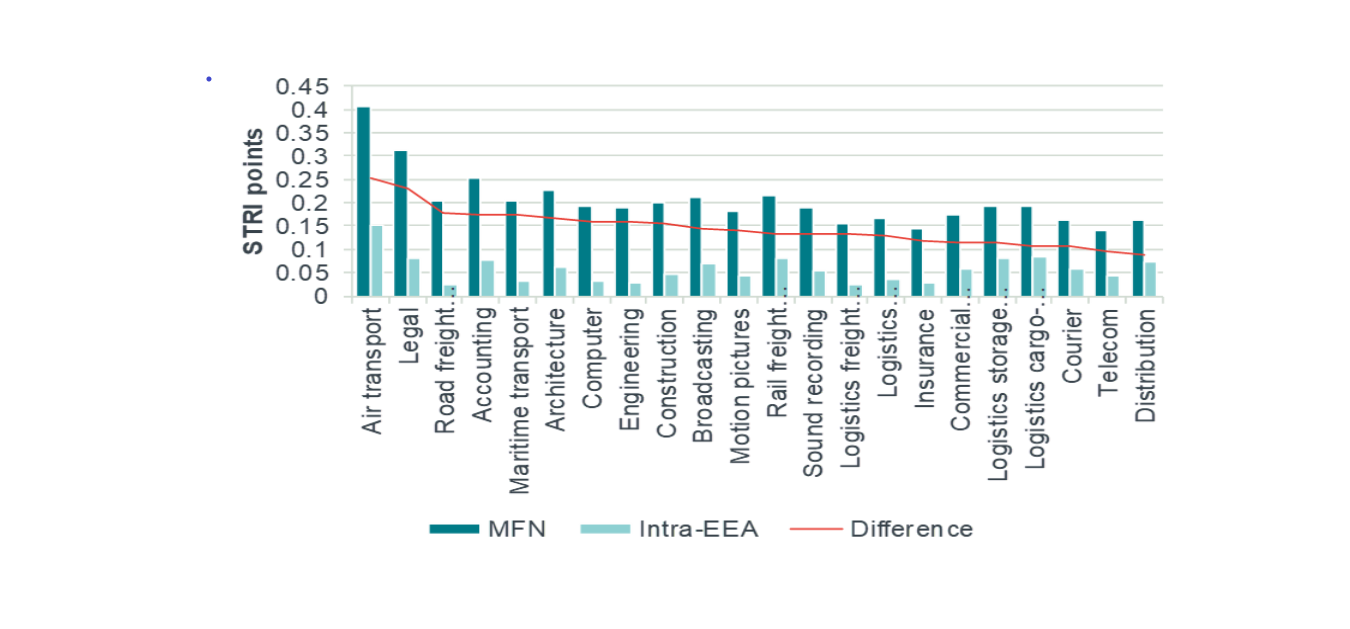

Data recently produced by the OECD allow us to measure the difference between services trade restrictiveness within the European Economic Area (EEA), and services trade restrictiveness that EEA members apply on a MFN basis. As already observed, because FTAs mainly involve bindings at applied MFN rates, the latter provide a rough approximation of the level of restrictiveness that the UK would face should it leave the Single Market and replace it with an arrangement on services modelled, say, on the Canada-EU FTA.

Figure 1 captures the differences between what UK exporters would face under the EEA, as at present, and under a MFN regime. Levels of restrictiveness are represented as an index, with 1 implying totally restricted services trade and 0 implying total liberalisation. The results reported are by service sector and on a trade weighted basis (i.e. weighted by UK-EEA trade).

The results show that in general EEA countries have liberal services trade regimes. But also that there is a significant gap between what they offer each other, on one hand, and what they offer those outside the single market, on the other. Service suppliers outside the single market can expect to face more restrictions.

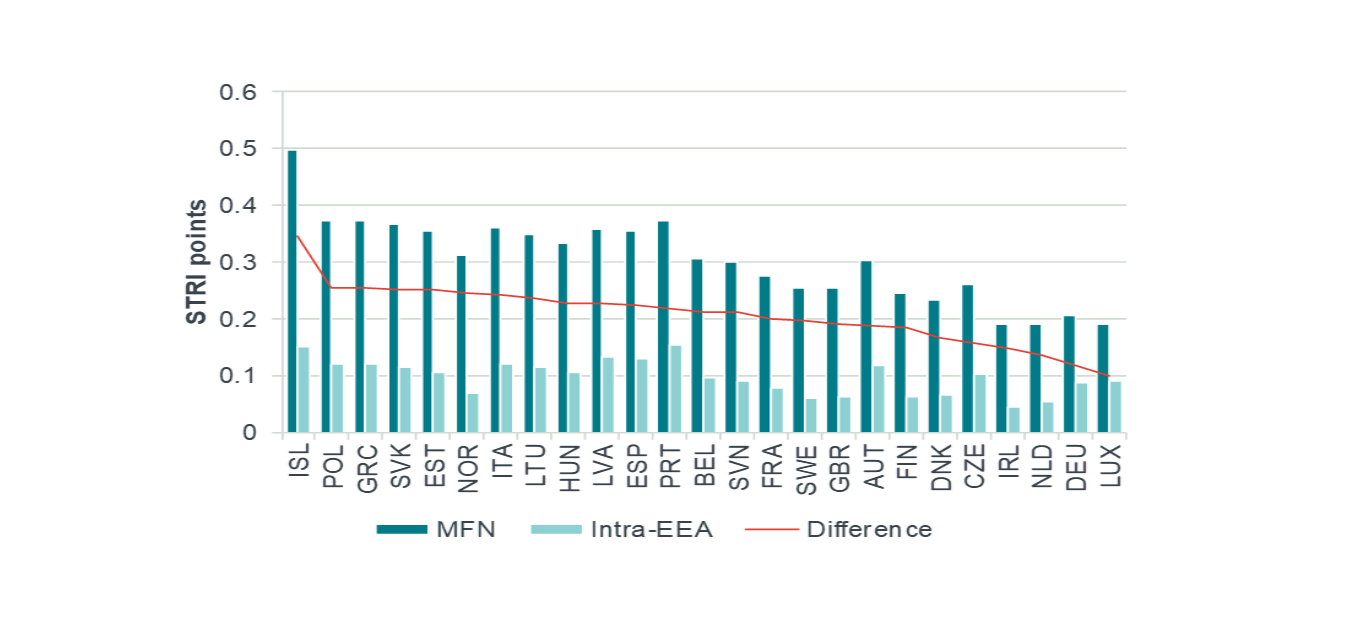

Figure 2 reports results for individual countries (country coverage reflects data availability).

The EU countries that matter most to the UK (in terms of shares of exports) are the Netherlands, Germany, Ireland and France. For the first three of these countries, the gap between MFN and EEA levels of restrictiveness is lower than the group average, which helps the UK.

Another point to note is the disparity between countries. This highlights the fact that services liberalisation tends to be country specific. This means that outside the single market, if the UK were to negotiate a free trade agreement that included services, it would need in effect to persuade each country to reduce its services restrictions from its applied MFN levels and towards those prevailing within the EEA. A glance through existing FTA texts will show that the first inclination of EU members when negotiating with non-EU members is largely to retain existing country-specific restrictions.

What is at stake?

What are these differences worth? To find out we used a gravity model of trade that measures the responsiveness of bilateral flows in services between the UK and the EEA countries to changes in levels of restrictiveness. The results are very significant. UK exports to the EEA countries fall by around £53 billion per year or around 42% of current levels. Imports from the EEA countries fall by around £31 billion, or close to 38% of current levels. The bulk of the effect on UK exports comes from six countries: France, Germany and Ireland ( around £8 billion per year each), the Netherlands (around £7.5 billion), Italy (£4.5 billion) and Spain (£3.5 billion).

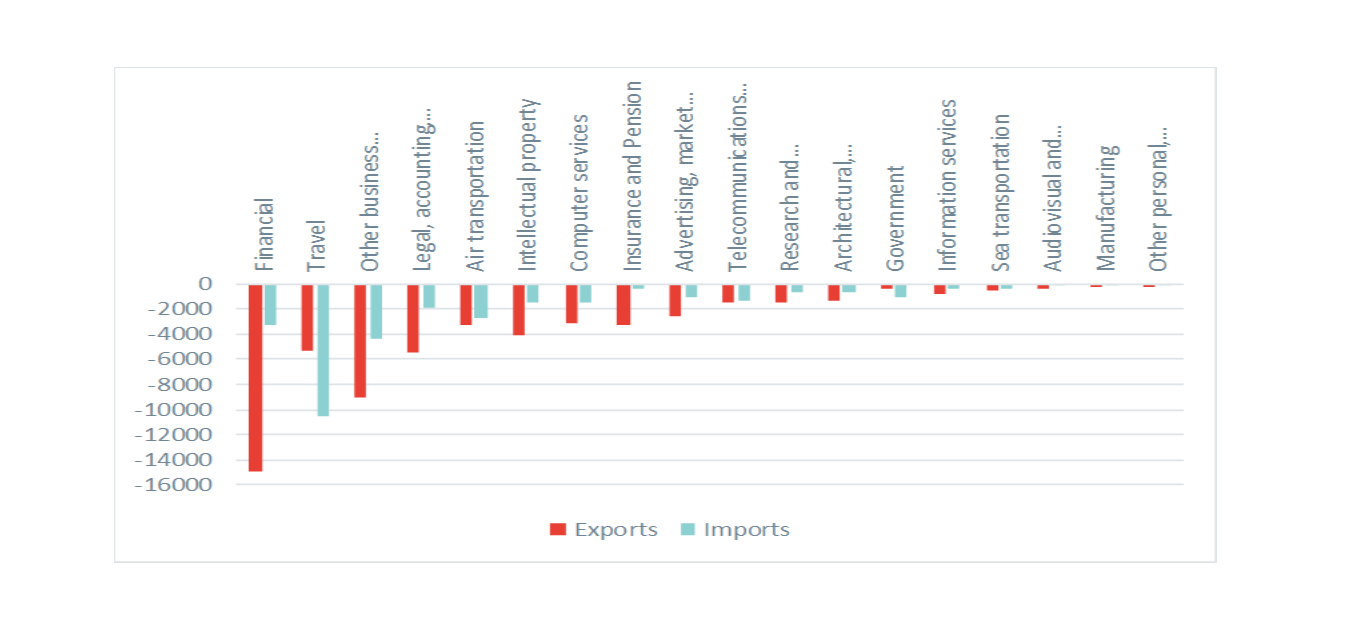

We can also break down these losses by sectors. The results are reported in Figure 3 below.

We observe a particular large effect on financial services and various professional services. Travel services is one area where the import effect (UK citizens travelling to EEA partners) significantly dominates UK exports.

The modelled impacts undoubtedly understate the true effects. We have not captured the effects of these restrictions on exports outside the EU. Exporters of both goods and services require enabling services, such as transport, logistics or telecommunications, and increasing the restrictiveness of these markets will affect exporters regardless of whether they export to the EU or outside this. Loss of access to labour skills, linked both to services trade and the wider concept of free movement similarly has effects that extend beyond UK EU trade.

Moreover, the results do not fully account for some other features of modern services trade. One of these is the extent to which being part of the EU’s single market can offer means of enforcing rules, and for redress, both vital conditions for modern services trade. Another is that these results do not fully capture the effects of policies towards data flows. As trade becomes more digital, the importance of regulatory frameworks affecting cross-border flows of data will increase in importance.

What are the options?

The results shed a spotlight on a key question that has largely gone missing in recent discussions, namely the issue of services trade. The reason this is so is less to do with the economics of the case, and much more to do with the political trade off proposed by the Government: accepting the loss of the single market for services in return for rescinding free movement. It is not a trade-off that either Government or Opposition seem open to revisiting.

Having said that, as demonstrated in the indicative vote process, there is some appetite within parliament to sponsor a solution involving integration with the single market. The results reported here point to some of the benefits of this approach. Moreover the pro-trade effects (not just on UK-EU trade but also on UK trade with the rest of the world) make deep integration on services something that the UK would want to consider if it genuinely seeks to get the most from an independent trade policy.

Outside of a single market arrangement, what are the things that the UK could do to at least limit the damage? One point to note is that when a country raises its services restrictions, this reduces its own exports. And indeed, both Frontier’s estimates and other research suggest that these self-inflicted effects dominate the effects of what other parties do. This result reflects a long-established finding (for goods as well as services) that import restrictions create anti-export biases.

So one option would be for the UK to mitigate its losses by unilaterally setting services restrictions to EEA levels even after it has left the single market. But doing so would also require that the UK reduce its restrictions on non-EEA partners to the same levels. This is because as a WTO Member, the UK is subject to the MFN obligation on services. It cannot selectively favour some WTO members over others. There is much to commend to unilateral liberalisation, but politically it is likely to be a hard sell, partly because it would be seen to affect the UK’s negotiating leverage with the EU and with non-EU partners. Moreover, whereas for goods, it is plausible for the government to temporarily change MFN tariffs to mitigate shocks, a similar approach is not possible for services. This is because measures affecting services trade are largely regulatory in nature. It is usually neither possible or desirable to change regulations on a temporary basis.

WTO rules do allow preferential liberalisation of services between partners as long as it is part of an agreement that covers all services sectors. The depth of liberalisation can vary across sectors and countries: that is for negotiators to decide. Because of this, and because not all countries matter equally across all sectors to the UK, one strategy for the UK could be to target the sectors in countries that really matter. Indeed, this is probably the thinking behind the position the UK Government has adopted. It probably thinks that because the UK is such a big player in services, at least some its partners will have strong incentives to negotiate.

The challenges for the UK would again be political, especially given the red lines set out by the current Government. It would need to identify what it could offer in return, most probably in the area of regulatory convergence. The EU is unlikely, for example, to accept deep liberalisation in road transport services without a common framework for, say, the health and safety of transport workers. It is also open to question how far the EU will agree to an approach that partially mimics the single market for services, for fear of affecting the integrity of the actual single market. Though clearly EU member states have their interests in services negotiations as well.

In conclusion, recent discussions have focused heavily on goods, and particularly on the question of a customs union. There are legitimate reasons as to why this is an important question. But the discussion, often conducted in “boo-hooray” terms, has detracted from the vital questions relating services trade. Inevitably, as negotiations regarding the nature of the UK’s future relationship to the EU proceed, these questions about services will come to the fore. Given their far-reaching impacts, a sharper focus on the issues by politicians and policymakers seems to be in order.

[1] Under the General Agreement on Trade in Services (GATS).

[2] The main benefit of these FTA services commitments is that they provide an added level of security: they prevent partners from rolling back existing liberalisation on services trade between them. They therefore represent an improvement over WTO commitments which in the most part allow for countries to undertake a significantly higher level of restrictions than they do in practice.